Tracking the Great Bear: How Environmentalists Recreated British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest

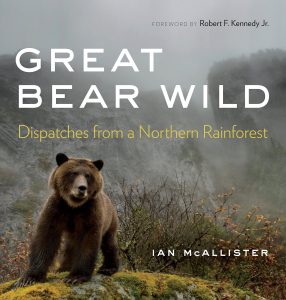

Great Bear Wild: Dispatches from a Northern Rainforest

Review By Max Ritts

February 24, 2015

BC Studies no. 188 Winter 2015-2016 | p. 148-150

Type “Great Bear Rainforest” into Google Earth and consider the long green slice of British Columbia’s coastline, now covered by the tricolour boxes of user-uploaded photo icons. Like so many conservation efforts, the story of the founding of the Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) is the story of its imaginary (its constructed identity and symbolism); how a once “empty” space become recognized as a spectacular production of nature. Upon entering the GBR, of course, one finds not pristine wilderness but a distinctive set of Indigenous Territories that, in Tracking the Great Bear, Justin Page calls “a dense tangle of ecological, economic, social, and political relations” (7). Like Ian McAllister’s photo-album, Great Bear Wild: Dispatches from a Northern Rainforest, Page’s book considers these relations and their role to the imaginary of the GBR. In different ways, both works provide opportunities to reflect upon the complex legacy of the GBR today.

Type “Great Bear Rainforest” into Google Earth and consider the long green slice of British Columbia’s coastline, now covered by the tricolour boxes of user-uploaded photo icons. Like so many conservation efforts, the story of the founding of the Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) is the story of its imaginary (its constructed identity and symbolism); how a once “empty” space become recognized as a spectacular production of nature. Upon entering the GBR, of course, one finds not pristine wilderness but a distinctive set of Indigenous Territories that, in Tracking the Great Bear, Justin Page calls “a dense tangle of ecological, economic, social, and political relations” (7). Like Ian McAllister’s photo-album, Great Bear Wild: Dispatches from a Northern Rainforest, Page’s book considers these relations and their role to the imaginary of the GBR. In different ways, both works provide opportunities to reflect upon the complex legacy of the GBR today.

Page showcases the creation of the GBR as an environmental institution-building exercise, an optimistic example of consensus-politics in an age of seemingly endless environmental struggle. He treads a well-worn path in BC environmental studies (kicked off by Braun, 2002) by suggesting that the GBR’s most distinguishing feature is its dissolution of the boundary between nature and society (9). To affirm this, Page employs Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to “follow the actors,” (13), by which he means the set of institutions (state, environmental, industrial, First Nations) that produced the landmark GBR agreements in 2006. In effect, these institutions successfully disentangled competing land use interests to achieve a rare conservation consensus.

Tracking the Great Bear book makes so much of ANT and of Latour’s Politics of Nature (2004) that a digression here is necessary. Latour’s aim was twofold: to dissect the concept of nature as an asocial, objective source of truth, and to use that insight to construct an environmental politics that recognizes nature(s) in the plural — by invoking a pertinent range of practices, events, things, and forces. Page’s sustained effort to valorize the GBR in this way is helpful. It allows him to isolate coalition-building as the environmentalists’ strategy vis-a-vis the region’s other interests and to affirm the role of conservation science: to consider how an Ecosystem-based Management (EMB) regime ordered the GBR’s complex natures into distinct “zones” (Chapter 1), and enrolled powerful non-humans (grizzly bears; Chapter 2) as regional political ambassadors.

But Tracking the Great Bear is so preoccupied with giving Latour’s stamp of approval to GBR that it ends up omitting a great deal. The text is peppered with ANT-isms, references to “scientific chains” and “cultural chains” (35), lengthy demonstrations of “interressement” (45), “occasions” (98), network “fragility” (104), and “matters of concern” (Chapter 3). There is no mention of other theoretical concepts — for example, class, Indigeneity, and colonialism — and how they might bear upon the history of the GBR. As a result, the book’s promise to reveal the GBR as a “powerful hybrid assemblage of humans and non-humans” (9) is unfulfilled.

Despite these reservations, Tracking the Great Bear will prove a good resource for scholars interested in contemporary environmental politicking. Page, an environmental consultant, knows his trade, and his interviews with environmentalists are detailed and consistently informative. They give the impression that the GBR is indeed a “tangle” of different relations — but to follow the metaphor, the reader remains unsure of how ongoing acts of “disentangling” have been enabled historically, geographically, and in the still un-ceded territories of Coastal First Nations.

Great Bear Wild suggests how one environmentalist is finding his way through the woods. Ian McAllister has been around the GBR longer than the concept existed. His first book Great Bear Rainforest (1997) helped to popularize both name and region, and established McAllister as a first-rate photo-documentarian. Great Bear Wild confirms these considerable photography skills: stunning shots of black bears (36) and coastal wolves (67), as well as surprisingly vivid captures of underwater reefs, anemones, and whales (81). For the most part, McAllister’s enviro-aesthetic remains familiar — lush, dramatic, unpeopled — and readers looking to discover what all the GBR-related fuss is about will be more than piqued by perusing these pages. In this respect, Great Bear Wild is on familiar ground, but compared with McAllister’s first book, Great Bear Wild suggests a development in the photographer’s appreciation of the region.

This revelation emerges in the tension between the text and the images. In the text, we get a far more intimate picture of life in the GBR than the bulk of the pictures permit. This is because McAllister displays a growing appreciation for the region’s original stewards, including the members of the Heiltsuk and Gitga’at First Nations he has come to know personally. The results are consistently insightful. McAllister’s prose reveals a place marked by the intersecting trails of grizzlies, salmon, and Indigenous fishermen; local histories built up by the patterning of seaweed harvesters and songbirds, and villages threatened by the arrogance of a government that continues to deprive First Nations of their sustainable livelihoods. As such, Great Bear Wild engages with the Latourian demand to contend with nature’s difference — and confirms for the GBR a panoply of life movements, events and, indeed, Latourian “occurrences.”

Certainly, it would be nice to see more of McAllister’s prose in McAllister’s photos. But Great Bear Wild’s best visual moments — for example, of Gitga’at fisherman Tony Eaton drying halibut woks (19), or of the annual herring spawn turning an entire Heiltsuk shoreline milky white (121) — contain the suggestion that a new representational aesthetic for the GBR is in the works. It is something worth looking forward to: a celebration of the entangling forms of human and non-human activity that continue to remake the region into the wondrous place it has always been.

REFERENCES

Braun, Bruce. 2002. The Intemperate Rainforest. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McAllister, Ian. 1997. The Great Bear Rainforest: Canada’s Forgotten Coast. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing.

Tracking the Great Bear: How Environmentalists Recreated British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest

Justin Page

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Nature | History | Society Series. 176 pp. $29.95

Great Bear Wild: Dispatches from a Northern Rainforest

Ian McAllister

Vancouver: Sierra Books, 2014. 192 pp. $50.00 cloth