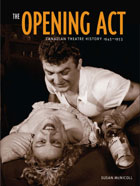

The Opening Act: Canadian Theatre History 1945-1953

Review By James Hoffman

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 176 Winter 2012-2013 | p. 182-3

The writing of Canadian Theatre History, as an academic field of study, is a latecomer, with the first wave of academic articles and books appearing only in the mid-1970s along with the founding the Association for Canadian Theatre History. In the first decade or so, until wide applications of critical theory added deeper cultural perspectives, many of the books, articles, and conference papers were little more than selected compilations of raw historical data, usually presented with a note of triumphant discovery — as if to say, yes, we have a Canadian theatre and here is convincing evidence that something important happened!

The Opening Act, as a richly detailed record of a hitherto little recorded period in our theatrical history, follows this same course, chronicling many of the personalities and companies of the post-war years until July 1953, when the Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada opened its first season of plays and marked, for many observers, the beginning of the country’s sustaining professional theatre. Susan McNicoll is correct in insisting that there was in fact much professional theatre happening in Canada during the years preceding that “glorious summer” and that its stories need to be told — and celebrated.

And stories she has, many of them, of pioneering and colourful thespians struggling with few theatres to perform in and perilously miniscule budgets to work with, nonetheless staging well-received productions of popular and, occasionally, Canadian plays. Most companies enjoyed only a scant golden year or two before folding or transmogrifying into another company. An example, described in colourful narrative, is the Ottawa Stage Society, which by its third play, the sell-out hit, Shaw’s Pygmalion, had developed a winning “love affair” with local audiences, surely abetted by exceptionally talented actors such as the eighteen-year old Christopher Plummer.

But by 1949, however, with expenses outrunning box office revenues, censorship issues (the company rented the La Salle Academy, a Catholic Boys’ School, and had to submit scripts to a priest for approval), and failed appeals, the Company faced closure — only to be followed by the formation of the Canadian Repertory Theatre, notable for premiering Canadian plays such as Mazo de la Roche’s Whiteoaks (attended by the Queen Mother), but also to sputter away in financial indebtedness by the mid-fifties.

A major strength of the book is McNicoll’s letting the players tell their own stories — indeed it was the discovery of theatrical clippings of her father, the actor Floyd Caza, that inspired the book. Accordingly, she interviewed about fifty theatre folk, including major figures like Christopher Plummer, William Hutt, and Amelia Hall, whose testimony alone lends primary credence to her point that significant professional stage work was done in this period, and that it constituted an important training ground for Canada’s subsequent, better known professional theatre. As Plummer states, in a chapter introduction, “It was one of the proudest, golden times of our kind of identity and creativity.”

There are many more figures, lesser known but important ones, some of whom will be familiar or at least certainly of interest to British Columbia readers, such as Thor Arngrim, Dorothy Davies, and Andrew Allan, and there are finely detailed narratives of Vancouver’s three important companies of those formative years: Everyman, Totem, and Theatre Under the Stars. This is an indispensible, highly readable compendium of the essential characters of a critical period in our theatrical history. The book is richly illustrated with around four dozen photos, many of them production shots, including some of Floyd Caza, to whom the book is dedicated.

While McNicoll has done very well in assembling the stories, she has not provided much in the way of documenting her materials, nor of acknowledging other pertinent sources. She quotes around fifty people, for example, but nowhere indicates the sources or dates of the citations; in addition, important published articles on some of the companies are not referenced or suggested as further reading, such as Denis Johnston’s article on Totem Theatre in Sherrill Grace and Jerry Wasserman’s Theatre and AutoBiography, or my own on Everyman Theatre in BC Studies Issue 76.

The Opening Act: Canadian Theatre History 1945-1953

By Susan McNicoll

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2012 330 pp, $24.95