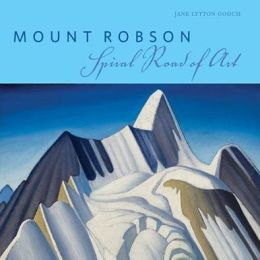

Mount Robson: Spiral Road of Art

Review By Maria Tippett

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 184 Winter 2014-2015 | p. 170-71

Over the past several years Jane Lytton Gooch has published books devoted to the sketches, paintings, and photographs inspired by the landscape of British Columbia and Alberta. Celebrating the centennial of the founding of British Columbia’s second oldest provincial park, Mount Robson: Spiral Road to Art joins her previous studies of Bow Lake, Mount Assiniboine, and Lake O’Hara.

At almost four thousand metres above sea level, Mount Robson is the highest peak in the Rocky Mountain chain and British Columbia’s second highest peak after Mount Waddington, which tops it by a mere sixty-five metres. Mount Robson is also one of the province’s most challenging mountains to climb. But Gooch is not only concerned with telling her readers what the mountain is composed of — sedimentary rock. Or where it is located — on the western edge of the Rockies near the headwaters of the Fraser River. Or when Mount Robson was first scaled — Conrad Kain, Albert MacCarthy and William Foster ascended the east side of the massif to reach the summit in 1913. Or even how the mountain earned its name — Gooch offers two theories: Mount Robson might have been named after a member of the North West Company in the early 1820s or, prior to that, named by an Iroquois guide, Pierre Hatsination. However, as with her previous studies, Gooch’s main concern is with the visual artists who have portrayed Mount Robson over the last one hundred and fifty years.

It was not uncommon for surveyors and explorers to include lightning sketches of landscape profiles and headlands in their official reports. However, few among these early nineteenth century visitors were — like the British-trained artist William Hind, who travelled through present-day Mount Robson Provincial Park with the Overlanders in 1862 — accomplished artists. Hind left a stunning album of watercolours and drawings rendered in the Pre-Raphaelite style depicting his journey through present-day British Columbia. A few decades later, Canadian-born A.P. Coleman not only sketched Mount Robson, but wrote about it too (The Canadian Rockies: New and Old Trails was published in 1911). A professor of Geology at the University of Toronto, the vice-president of the Alpine Club of Canada and a well-seasoned climber in the Rockies and Selkirks, Coleman and his brother, Lucius, made two unsuccessful attempts to reach the summit of Mount Robson in 1907 and 1908. Nevertheless, the ice-blue glaciers that the artist captured from a height of 11,000 feet certainly impressed the Ontarians who had been viewing Coleman’s mountain landscapes at the annual exhibitions of the Royal Canadian Academy since the middle of the 1880s.

A.P. Coleman’s paintings offered a visual challenge to a later generation of artists, notably the better-known painters associated with the Ontario Group of Seven. A.Y. Jackson and Lawren Harris first painted Mount Robson in 1914 and 1924, respectively. And, as Gooch admirably demonstrates, Mount Robson continues to inspire a host of artists to capture its lakes and glaciers, its alarmingly steep rock faces, and its mountain peak.

Gooch might also have asked whether or not it is possible for an artist to avoid giving a chocolate-box rendering of Mount Robson — or, for that matter, of any mountain in the province. She does not fully consider how an artist with abstract leanings might capture Mount Robson; nor does she explore whether any of the region’s First Nations artists have attempted to incorporate their iconography into a rendering of the province’s second highest mountain.

Two aspects dominate the paintings, photographs, and sketches illustrated in this slim volume. One approach presents a distant view of Mount Robson, showing it anchored by smudged forest-clad side-wings, a screen of realistically rendered trees, or a body of water. The other offers a more focused view of the upper regions of the mountain. These conventional ways of rendering mountain landscape, first evident in the work of C. P. Coleman, can be seen in Mel Heath’s Berg Lake, Mt Robson (c. 2010); Norene Carr’s North Face, Mt Robson, Berg Lake (1988); Glenn Payan’s Kain Face, Mt Robson (2010) — a washed out version of Lawren Harris’s monumental 1929 oil sketch, Mount Robson from the South East; and Glen Boles’ more successful, Mt Robson North Face (2009).

True, there is one notable work among the images gathered together in Mount Robson: Spiral Road to Art that, in this reviewer’s mind, avoids the conventional clichés characteristic of mountain paintings and photographs. Canadian Alpine Club Mount Robson Climb, 1913 is not a painting but a photograph. It was not taken recently but, as its title indicates, one hundred years ago. This is tantalizing — for, while we know that the picture was taken by a member of the Alpine Club of Canada, we do not know the photographer’s name. Mount Robson thus maintains its image of mystery.

Mount Robson: Spiral Road of Art

By Jane Lytton Gooch

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2013. 240 pp. $25.00 paper