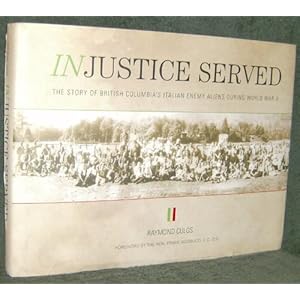

InJustice Served: The Story of British Columbia’s Italian Enemy Aliens During World War II

Review By Stephen Fielding

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 182 Summer 2014 | p. 235-234

Historical redress is a touchy subject and should be handled with care. At root, it is a question about what to address. InJustice Served is funded by the vaguely termed “Community Historical Recognition Program” (CHRP), the Canadian Government’s five-year effort to revisit uncomfortable moments in its past. It is part of a larger project that re-examines the experiences of so-called Italian enemy aliens during the Second World War.

The Italian word for the study of history is La storia, literally meaning “the story.” InJustice Served conveys the truest sense of the word. Like Culos’s earlier writings, the chapters are thematic and chronological, readable and intimate. Many of the personal accounts are drawn from his first survey, Vancouver’s Society of Italians Volume I, but they find new life in this comprehensive coffee-table format. The author’s storytelling style effectively places the larger forces of geo-political conflict, home front anxieties, and Italian community tensions at a level of lived experience.

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Canada and its allies. Two days later, Canadian Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe declared illegal all “politically and nationalistically skewed [Italian Canadian] organizations.” The RCMP arrested 632 Italian-Canadian men, forty-four of them from British Columbia, and sentenced them without trial to three internment camps. They were destined to spend an average of fifteen months under military supervision. The other Italian “enemy aliens” in the province were Italian nationals ordered to leave the Pacific Coast and some 900 Italian residents required to report monthly to the RCMP (18). Vancouver was the fulcrum of pro-fascist activity in British Columbia, alongside a smaller pocket in Trail. The fascist question primarily concerned the activities of the club Circolo Giulio Giordani. Formed in 1927 and knitted together by an oath to Mussolini and support from the Italian vice-consul, the Giordani trumpeted the virtues of Fascist Italy through meetings, youth activities, propaganda film nights, and a local newspaper. Members took pride in Italy’s political and economic resurgence, particularly in response to the discrimination they faced in Canada. However, Culos contends that beyond the Giordani element, “pro-Canada was the majority sentiment of the Italian Colony” (18). Even those interned for their fascist leanings ranged from “strongly committed, otherwise naïve, [or] innocent” (19-20, 64).

Italy’s war with Canada exposed fractures in Italian-Canadian communities. Pro-fascist and anti-fascist sides were already clashing in local newspapers and club politics, and some discovered in the theatre of war an opportunity to frame an adversary. Such tragic outcomes were possible because the RCMP relied heavily on community informants to select internees, a practice hauntingly showcased in the new CHRP-funded play “Paradise by the River.”

The book has its surprises. Chapter 9 tells the sad irony of a man serving in the Air Force while his father was quarantined at Kananaskis, Alberta (144). We also learn that internment had its sunnier features. Guards were generally quite amicable and lenient to the Italians, joining them in a game of cards or glass of wine. Neither were camp responsibilities or mealtimes cumbersome. One man left the compound healthier and twenty-five pounds heavier than the day he arrived. Internees admitted that their loved ones suffered greater hardships, struggling to raise children and support households in the absence of a husband, father, son or brother.

The book ends on a surprising note, asking “Was justice served?” The author has already answered the question in the title. Justice was certainly not served to the internees, who regardless of political fealty were denied legal counsel and habeas corpus. Is Culos suggesting that the state committed a greater “crime against ethnicity?” This was the argument made by the National Congress of Italian Canadians and contained in Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s official apology in 1990. Other writers have since challenged this view. The question simplifies the author’s implicit point that the Canadian government pursued suspected fascists and not Italians per se, but evidently humiliated Italian Canadians well beyond the activities of a fascist minority.

It is sad, but perhaps fitting, to discover that all of the interned British Columbian Italians passed away before the writing of this book. They never lived to see their stories in print. Yet somehow in their absence, and in the spirit of Italian storia, InJustice Served guarantees that their stories will live on.

References

Culos, Raymond. 1998. Vancouver’s Society of Italians, vol. I. Vancouver: Harbour Publishing.

Paradise by the River. 2010. By Vittorio Rossi. Directed by Marianne McIsaac. Richmond Hill, ON: Shadowpath Theatre Productions, based on Rossi, Paradise by the River. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1998.

InJustice Served: The Story of British Columbia’s Italian Enemy

Italians during World War II

By Ray Culos

Montreal: Cusmano Books, 2012. 216 pp. $50.00 cloth.