Edenbank: The Story of a Canadian Pioneer Farm

Review By Morag Maclachlan

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 144 Winter 2004-2005 | p. 142-4

ALLEN WELLS, who came west from Upper Canada for the gold rush, stayed to farm, establishing Edenbank, one of the earliest and largest farms in the Chilliwack Valley. As new settlers arrived, he encouraged “the right type,” and, as a result, he played an important role in establishing Sardis as a community indelibly shaped by Methodist values and conservative political views.

ALLEN WELLS, who came west from Upper Canada for the gold rush, stayed to farm, establishing Edenbank, one of the earliest and largest farms in the Chilliwack Valley. As new settlers arrived, he encouraged “the right type,” and, as a result, he played an important role in establishing Sardis as a community indelibly shaped by Methodist values and conservative political views.

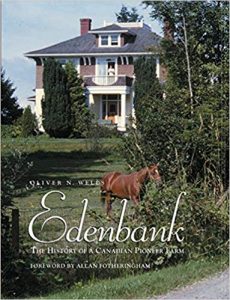

Oliver Wells, one of Allen’s grandsons, took over the farm from his father, Edwin, and wrote a history of Edenbank before his untimely death in 1970. The work has been published because of the support Harbour Publishing gives to local history and because of several publishing grants but largely because of the persistent efforts of Oliver’s daughter, Marie Weeden, who did further research, elicited help from a number of people (including her husband who shared the work of editing) and produced a handsome book. With a colourful jacket and at least one black-and-white picture on almost every page, Edenbank is a thing of beauty and provides a pictorial as well as a written record.

One of the most important contributions this book makes to local history is the insight it gives into many aspects of farming, from milking to haying and harvesting, from raising animals – cows, horses, pigs, sheep, and poultry – to methods of housing and feeding them as well as the skills involved in slaughtering them. It also provides an important record of the many changes in agricultural practices over the years. The publication of this family history is important at a time when Edenbank is a housing estate and when urban sprawl has eliminated so much of the dairy farming that was once so vital to the economy of the lower Fraser Valley.

Although Oliver Wells was largely responsible for establishing the Chilliwack Historical Society for the purpose of establishing a museum and an archives, both very successful projects, he had no training as a historian, and his research was based mainly on personal experience, family lore, and family papers. One example of this amateur approach can be found in his discussion of seasonal flooding, one of the hazards faced by Chilliwack Valley farmers. He recounts some experiences and discusses the tactics used to protect the land. Then (146) he mentions that the Chilliwack River changed course, failing to explain that the Wellses and some of their Sardis neighbours caused the change by blocking the river so that the water flowed down to Atchelitz. The vigilantism and the court cases that followed go unmentioned, although there is a vague reference to a third-hand account of the troubles (63). Sardis people remembered the valiant struggle against the floods, but bitter memories lingered for years in Atchelitz.

Although Wells had no background in linguistics, he attempted to record the language of the local Native people. Two positive things resulted from this venture. He recorded many of the local legends, which were later published by Marie Weedon with the assistance of Ralph Maud and Brent Galloway, and he and his wife also played an important role in the revival of Salish weaving. He claimed that his interest was piqued when he was asked to write an introduction to the “Sepass Poems,” a collection of local Native legends that Eloise Street claimed to have received from Chief Sepass, an indication that he accepted without question a story that academics found highly dubious.

It is highly likely that he was even more influenced by his knowledge of the policies practised at Coqualeetza, a residential school for Natives that was established by the Methodists. Although the school had a fine reputation and many grateful graduates, children were forbidden to speak their own language and no local children attended. The Stô:lô, among the last to have close contact with Europeans and the first to experience the debilitating effects of white settlement, were considered inferior to other Native groups. Coqualeetza looked to the north for students, producing many graduates who have been very vocal about their happy experiences there, including several First Nations leaders, Frank Calder, Guy Willaims, and Hattie Ferguson among them. Wells, interest in his neighbours was obviously an attempt to make up for their earlier exclusion.

This family history reveals a great deal about Wells himself. He was no academic and he attempted some things for which he had insufficient background, but his heart was in the right place and he left the world better for his presence. By maintaining a prize herd of Ayrshire cattle and by responding to change, he upheld the reputation for progressive farming first established by his grandfather. And by seeking to beautify Edenbank he fulfilled his father’s aspirations to create an atmosphere that would live up to the name of the farm. His strong sense of place, his love of the land, his quiet satisfaction in life as a farmer, and his concern for others are all qualities that are clearly evident. In concluding his history, Wells appears to be a man at peace with himself. He treasured his inheritance and he did his best to right wrongs. One can only agree with Allan Fotheringham, who wrote the introduction to the book, that Wells “set an example of how fine a man could be.”