Back to the Land: Ceramics from Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1970-1985

Review By Maria Tippett

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 181 Spring 2014 | p. 147-48

Earning a decent living from pottery is difficult. Crafts, in general, do not support high earners. The notion that any amateur can throw a pot has kept professional potters just above the poverty line — or in some cases, just below it. Given the challenges to the urban potter, it is perhaps not surprising that when the back-to-the-land movement arrived around 1970, a new generation of rustic potters emerged. Now, with more than a generation separating us from the end of that movement in 1985, we have the hindsight to examine the phenomenon.

Any book or catalogue accompanying an art exhibition needs to consider the objects on display in their cultural, social, and political context. And if any art historians find themselves ill equipped to look beyond the canvas, sculpture, video — or in this case the ceramic “pot” — they can conscript others to help them. Parcelling up the task in this way can result in conflicting agendas, thereby leaving the reader in search of an overarching theme. More happily, as with the book under discussion, Back to the Land: Ceramics from Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1970-1985, more than one viewpoint can give breadth and understanding to the subject at hand.

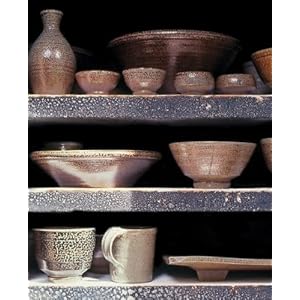

Nancy Janovicek is an historian at the University of Calgary whose research on the back-to-the-land movement in British Columbia is well suited to a discussion of pottery-making between 1970 and 1985. Situating potters within the rural counterculture movement, Janovicek considers New Left ideologies, rustic home building, child rearing, health foods, and farming practices, along with American civil rights, the Vietnam War, and religious and sexual practices as part of what she calls “countercultural experiments.” As she writes, the movement “shared three common goals that were crucial to individual and social liberation: decentralization and local control over governance; self-reliance and mutual aid; and development of alternative economic models that rejected mass production and dangerous technological development” (10). Janovicek’s essay admirably sets the stage for Diane Carr’s discussion of pottery-making on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in the same period. A former pottery-shop owner — she ran Victoria’s Potters Wheel during the 1970s — Carr is well qualified in writing about the economics of pottery making, art schools, and potters’ guilds, as well as in providing short biographies of the potters themselves. She is best, however, when she writes about the influences that have shaped pottery-makers’ artistic styles and philosophies. Carr shows, for example, how Ian Steele and Wayne Ngan were committed, like their mentors Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, to raising “the humble utilitarian pot to an almost mystical status, and the work of the potter to a spiritual pursuit of beauty, harmony, and simplicity” (27). She demonstrates how Jan and Helga Grove’s connection to European modernism made them adhere in their work to the German Bauhaus’s famous mantras, “form follows function” and “less is more.” And she tells us how Walter Dexter, among others, departed from the “demanding discipline of repetitious production,” by following the experiments of the Abstract Expressionist painters in the United States (45). Although the counterculture movement is now over, potters like Wayne Ngan, among others, continue to produce work within the three stylistic categories as charted by Carr. Many rustic potters are still working outside of the specific ideological circumstances of the period that Janovicek writes about. The low financial rewards of potting seem to have natural affinities with a counter-culture lifestyle, especially one pursued outside of the urban setting. Is it too materialistic to observe that making pottery is inherently a messy business? After all, building a kiln is dangerous; few city-dwellers want one in the backyard — and even fewer of a potter’s neighbours.

Back to the Land: Ceramics from Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1970-1985

By Diane Carr and Nancy Janovicek

Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2012. 95 pp. $29.95 paper.