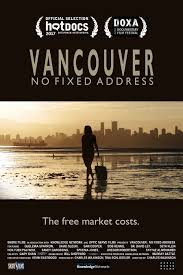

Vancouver: No Fixed Address

Review By Patricia Wood

February 4, 2019

BC Studies no. 201 Spring 2019 | p. 165-166

What stays with you after watching Charles Wilkinson’s new documentary, Vancouver: No Fixed Address, is its beautiful cinematography. Vancouver’s ideal location at the intersection of the ocean, the mountains, and the sky is captured brilliantly: every shot is framed well, whether it is day, night, or twilight. The light hits the water exquisitely; the sky has that rich, late-afternoon glow. It’s not just the harbour views: the studio interviews, the landscapes, the aerial views all have perfect composition, perfect lighting.

What stays with you after watching Charles Wilkinson’s new documentary, Vancouver: No Fixed Address, is its beautiful cinematography. Vancouver’s ideal location at the intersection of the ocean, the mountains, and the sky is captured brilliantly: every shot is framed well, whether it is day, night, or twilight. The light hits the water exquisitely; the sky has that rich, late-afternoon glow. It’s not just the harbour views: the studio interviews, the landscapes, the aerial views all have perfect composition, perfect lighting.

That the film does such a fine job holding the gaze will, hopefully, help the audience remember the stories as well. Although the title of the film suggests the focus is homelessness, the scope is actually broader. Through a series of diverse portraits of residents, the film presents several experiences and perspectives on the difficulties of living in Vancouver. The speakers include Indigenous people, residents whose families have lived there for generations, immigrants, and the children of immigrants. We meet Millennials sharing a house, a guy living on his boat, another man living in his van, a Tiny House builder, old and new suburbanites, and high-rise dwellers.

The success of this film is that it puts a human face on Vancouver’s housing crisis and invites us to consider what our goals and values are. David Suzuki, for example, asks if a city is still a city if it makes no room for seniors or young people. The expense of finding housing is a central frustration, but other aspects are explored which demonstrate how limited choices come to shape people’s lives and expectations about belonging to a place and having a “home.”

Through the addition of expert commentary from scholars and journalists, the situation is also set in several contexts, including the city’s ecology, the history of racism in Vancouver, the personal and familial, and the city as a site within the global flow of capital, particularly out of China. An insightful connection is made, by a Chinese immigrant herself, between the relocation of manufacturing from North America to China, the resulting pollution in China, and the subsequent desire of Chinese to move to the cleaner air of Canada.

The film opens and closes with comments from Quelemia Sparrow, an actor from the Musqueam Nation. She raises the larger question of how Vancouver’s tortured housing and homelessness crisis is playing out within unceded Indigenous territory, where the first inhabitants were burned out of their homes to create Stanley Park. What does it mean for settlers to make a home here? This is an important discussion and I would have liked to see it more actively connected to the rest of the film, which has only one other brief story from an Indigenous person.

The film is a cinematic collage more than a linear narrative driving towards a clear purpose. The sharpest moment in the film is the cut from a couple celebrating their purchase of a north shore condo with champagne, to a 67-year-old man who lives in his van. This juxtaposition speaks most directly to the viciously unfair distribution of opportunities. The overall impression at the end of the film is that the situation is a mess, with many costs.

Solutions are less clear. The film’s tag line, “Free markets cost,” implies a wish for the state to get more involved but there is little advocacy for this in the film. Vancouver mayor Gregor Robertson mentions the need to build housing and to use taxes as disincentives to speculation. The conclusion of the film hints vaguely at mobilization of “the people,” with a shot of a housing protest and comments from journalist Sandy Garossino about how the idea of Occupy started in Vancouver.

The film’s coverage of multiple perspectives of residents and experts makes it a valuable complement to general news coverage, and an excellent candidate for an undergraduate class on urban economic and social geographies, especially housing. There’s a nice theme of live musicians who play in their homes or on the street–piano, Chinese harp, drums, electric guitar, banjo. They play individually in bridging interludes between scenes, and then are overlaid at the end of the film to play “together.” As a metaphor for the city, it’s not a bad one.

Publication Information

Vancouver: No Fixed Address

Charles Wilkinson, Tina Schliessler

British Columbia: Shore Films, 2017. Film.