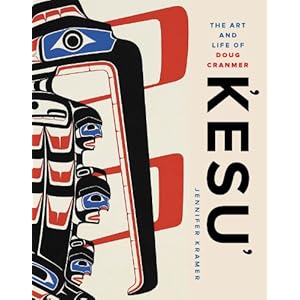

K’esu’: The Art and Life of Doug Cranmer

Review By Carolyn Butler Palmer

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 181 Spring 2014 | p. 155-57

Jennifer Kramer’s book K’esu’: The Art and Life of Doug Cranmer was written to accompany the Museum of Anthropology’s 2012 landmark retrospective exhibit about the life and work of the internationally renowned Kwakwaka’wakw artist Doug Cranmer (1927-2006). As Kramer’s book is focused on the life of a single indigenous artist, it makes a significant contribution to a rare genre of Northwest Coast indigenous artist biography exemplified by the works of Doris Shadbolt, Maria Tippett, Bill Reid, Martine J. Reid, Ulli Stelzer, Karen Duffek, Charlotte Townsend-Gault, Ian Thom, James P. Spradley, Phil Nuytten, Bill Holm, Harry Assu, and Joy Inglis. Incorporating the memories and photographs of Cranmer’s family and friends, K’esu’ is a textual commemoration of his life displaying the observations of those who knew him well. The book’s value is most clearly expressed in the intimate tone of the final chapter, “Mentor,” in which family and friends tell the story of Cranmer’s last days.

Kramer’s book opens with forewords by Anthony Shelton of the Museum of Anthropology (MoA) at UBC, and by Gloria Cranmer Webster, Doug Cranmer’s eminent younger sister. Together, these essays map important cultural points in the constellations of his life, including his international travels, Cranmer family history, and the volatile history of potlatching. We also learn how Doug Cranmer acquired the name K’esu’, or “wealth being carved.”

As the book is a textual memorial, it is most appropriate that Kramer deploys the quadripartite structures of Northwest Coast storytelling convention in the four chapters that constitute the main part of the book. The first chapter, “Pragmatist,” begins with Cranmer’s life in Alert Bay, where he watched carvers such as Arthur Shaughnessy, Sr. and Frank Walker. Kramer points out that Cranmer’s carving career did not unfold in a predictable fashion as a hereditary carver destined to serve Kwakwaka’wakw nobility. Instead, Cranmer appears as an artist who initially made his living in the fishing and lumber industries, for lack of opportunities to carve during the 1930s and 40s, while the ban on the potlatch was in full force. His carving career began after the ban was quietly erased in 1951, and he worked with Mungo Martin in Victoria and then with Bill Reid in Vancouver. Cranmer’s carving career also depended upon his ability to support himself financially. During the 1960s and 70s, as the potlatch culture was regaining its hold, he was able to tap into Vancouver’s commercial art and souvenir markets through his partnership in one of Vancouver’s first Native-owned commercial art galleries, The Talking Stick.

Chapters Two and Three enlarge on Cranmer’s life as an established artist by detailing the various elements that contributed to his success: the Talking Stick, friendship with MoA curators and UBC anthropologists, and his noble rank in Kwakwaka’wakw circles. At the same time, Kramer calls attention to details of his personality: Cranmer was a nobleman who did not especially like potlatching; a carver who called himself a whittler; a commercial artist who did not like to sign his work, though his signature would contributed to its market value; and an artist who melded elements of abstract expressionism forwarded by Japanese Canadian artist Roy Kiyooka with conventional elements of Northwest Coast design. Thus, Kramer pieces together a significant social history of Northwest Coast art that shows Cranmer as a member of many seemingly separate social circles, including carving, High Modernism, and craft. Kramer implicitly raises important questions about the discursive practices that enforce distinctions between these seemingly different communities.

The fourth and final chapter, “The Mentor,” focuses on Cranmer’s 1977 return to Alert Bay, where he lived out the rest of his life. Like Gloria Cranmer Webster’s foreword, this final chapter is heavily inflected with the personal recollections of the students Cranmer taught in the basement of the building that once housed St. Michael’s residential school, including Gerry Ambers, John Livingston, and Calvin Hunt, who tell the story of an artist who cared more deeply about aesthetic principles than the commercial value of his work, and who dedicated himself to instilling the same sensibility in his protégées.

In the “Afterward,” Kramer draws together threads of an argument implicit in the whole. She calls explicit attention to the complex cultural intersections negotiated by an artist drawing his inspiration from Kwakwaka’wakw stories, living in the context of Vancouver’s transnational sensibility, and embracing Modernist principles of formalism and individualism, while eluding classification in any of these overly simplified categories. Beautifully illustrated with photographs of Cranmer’s art and family snapshots, K’esu’: The Art and Life of Doug Cranmer lovingly commits the memories of Doug Cranmer’s life to text for his friends and family while it introduces those who did not know him personally to his life and legacy. As a scholar of Native art studies, I would have appreciated more detailed documentation of source material deployed within the text, yet Kramer’s is one of a few recent studies that promote a renewal of interest in the lives of Northwest Coast Native artists.

REFERENCES

Assu, Harry, and Joy Inglis. 1989. Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Duffek, Karen, and Charlotte Townsend-Gault, editors. 2004. Bill Reid and Beyond: Expanding on Modern Native Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Holm, Bill. 1983. Smoky Top: The Life and Times of Willie Seaweed. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Nuytten, Phil. 1982. The Totem Carvers: Charlie James, Ellen Neel, and Mungo Martin Panorama Publications.

Reid, Martine J. 1998. Bill Reid and the Haida Canoe. Madeira Park: Harbour

Reid, Bill. 2009. Solitary Raven: The Essential Writings of Bill Reid. Toronto and Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

Shadbolt, Doris. 1998. Bill Reid. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Spradley, James P. 1972. Sewid: Guests Never Leave Hungry: The Autobiography of a Kwakiutl Indian. Montreal and Kingston: McGill and Queens University Press.

Stelzer, Ulli. 1994. Eagle Transforming: The Art of Robert Davidson. Vancouver and Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre.

Stelzer, Ulli. 2006. The Spirit of Haida Gwaii: Bill Reid’s Masterpiece. Toronto and Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

Thom, Ian, and Robert Davidson. 1993. Eagle of the Dawn. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Tippett, Maria. 2004. Bill Reid: The Making of an Indian. Toronto: Vintage.

K’esu’: The Art and Life of Doug Cranmer

By Jennifer Kramer with Gloria Cranmer Webster and Stolen Roth

Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre and UBC Museum of Anthropology, 2012. 160 pp. $29.95 paper.