Fishing the River of Time

Review By J.F. Bosher

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 182 Summer 2014 | p. 230-231

Here is an entertaining addition to the shelf of books about Vancouver Island. Depending upon the reader’s own experiences in life, and the breadth of his interests, he may be amused by Taylor’s rambling memories of fishing in the Cowichan Valley in the early 1960s and again forty years later, or by the pot pouri of thoughts about life which leak out of Taylor on nearly every page. “I am here to review every aspect of life and,” he tells us (21), “I have found I do that best while fishing. For many of us, going into the bush, climbing mountains or canoeing down rivers are ways of coming to terms with reality.” He fishes for much the same reasons that Michael Kitchen does in the film series, “Foyle’s War.” But “reality” for Taylor is far from simple. An adventurous British professor of geology who has settled in Australia after many travels, he worries about global warming and thinks about life on Vancouver Island as what he calls “the mystery of the great batholith” (171). Why, he wonders, does all this flora and fauna grow so abundantly on its massive bed of acid granite? And why is Australia so different?

What prompts the author to write is an unexpected chance to spend a few days with his eight-year-old grandson, Ned, whom he has never met before because the family dispersed when he and his wife divorced. Half way through the book Ned arrives in the care of Taylor’s son, Matthew. We learn nothing about Matthew; it is Ned who interests the author. We are treated to Taylor’s reflections about children and how to deal with them. While they are out fishing, he gently and indirectly tries to interest Ned in the great world. “My grandson and I had been exploring one of the outer layers of a ball of iron hurtling relentlessly through space. Although the locals called this piece of water the Cowichan and our species called this globe the Earth, the most obvious layer is water” (204). It is in this context that he thinks about the Cowichan River and the life around it.

Readers will interpret this book in various ways. For me the most interesting passages were Taylor’s comments about other British emigrants on the island: Roderick Langmere Haig-Brown (1908-1976); Lieut.-Colonel Dr. Richard Nugent Stoker (1851-1931); Raymond Murray Patterson (1898-1984), an author from County Durham in England; Henry March (1866-1950) from Rochdale, Lancashire, and others. Strange to relate, Taylor knows almost nothing about Robert Aubrey Meade (1852-1912), whose cabin he lived in for some years, about twenty-five miles from Duncan. This is a pity, as he might have enjoyed the story of this “remittance man” from Suffolk who had tried unsuccessfully to grow coffee in Ceylon, habitually drank champagne, was called out of his cabin to meet distinguished visitors because he owned the only formal dress-suit in the district, and was a descendant of the impoverished earls of Clanwilliam. Son of a British army officer from the Isle of Madeira and a woman born at Penang on the Malay coast, Meade was a second cousin of Admiral Richard James Meade, RN (1832-1907) and of Sir Robert Henry Meade (1835-1898), permanent under-secretary at the Colonial Office. [see John Bosher, Imperial Vancouver Island: Who was Who 1850-1950 (2nd ed., 2012, Woodstock, Oxfordshire), pp. 403-4].

These contacts show that Taylor lived instinctively in a British circle. Even the American, James Scott Negley Farson (1890-1960), to whom he often refers, lived in England for many years, joined the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War, married a niece of Stoker’s brother, Bram Stoker, and died at home in Georgetown, North Devon. As Taylor writes (73), Farson “considered himself an Englishman,” spent some years on Vancouver Island, and published a book about it, Going Fishing (1946), of which Taylor speaks highly. Although he does not seem to think of himself in these terms, Taylor turns out to be another of those English emigrants who feels at home on Vancouver Island, even though he has settled in another part of the Empire. The Canadians who invaded the Island in such numbers during the Second World War no doubt felt uncomfortable with him, and the feeling was certainly mutual. But Taylor carries on “irregardless” (as my students at Canadian universities used to say), his mind flooded with thoughts about the great outdoors he loves so much.

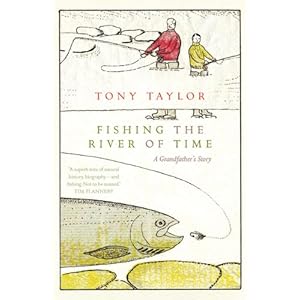

Fishing the River of Time

By Tony Taylor

Vancouver, Greystone Books, 2013. 216 pp. $19.95 paper