Red: The Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship, 2013

Review By Geoffrey Carr

December 5, 2016

BC Studies no. 195 Autumn 2017 | p. 180-181

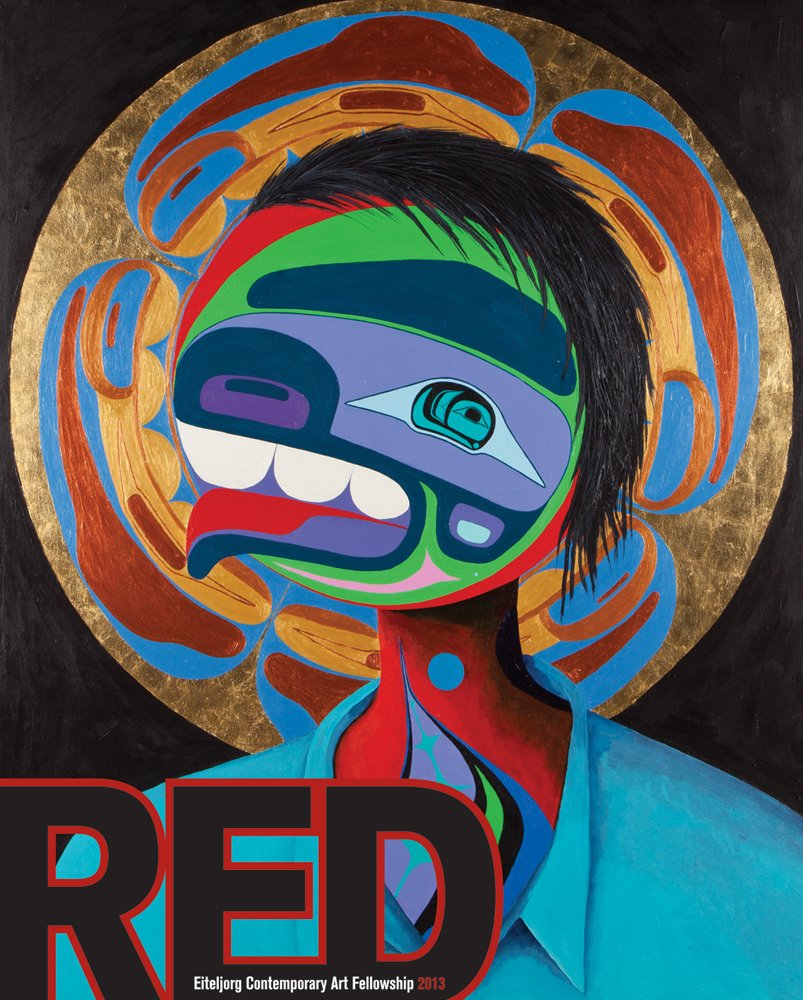

The short title of the book – Red – shares its name with the 2013 Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship for Native American Fine Art, which gathered together the work of five notable Indigenous artists: Julie Buffalohead (Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma), Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Aleut), Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee), Meryl McMaster (Plains Cree/Blackfoot), and the Eiteljorg Museum’s invited artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (Coast Salish/Okanagan).

The short title of the book – Red – shares its name with the 2013 Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship for Native American Fine Art, which gathered together the work of five notable Indigenous artists: Julie Buffalohead (Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma), Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Aleut), Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee), Meryl McMaster (Plains Cree/Blackfoot), and the Eiteljorg Museum’s invited artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (Coast Salish/Okanagan).

Of course, the title Red also conjures Vine Deloria, Jr.’s (Standing Rock Sioux) use of the word – “red power,” God is Red (1973), Red Earth, White Lies (1995) – not only to mobilize resistance by Indigenous peoples but also to articulate the intellectual means by which colonial societies oppress. The artworks included in Red demonstrate that the issues raised fifty years ago by the Red Power movement – sovereign control of territories, environmental degradation of lands, custody of children, broken treaties, and much more – continue to vex today. Additionally, though, the five Eiteljorg fellows also address emerging concerns shaped by poststructural and postcolonial forays into identity politics, cultural hybridity, cultural appropriation, playing Indian, and survivance.

Illustrations of the fellows’ artworks find support from five corresponding essays that examine each artist separately. The authors – heather ahtone (Chickasaw Nation and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma), Dana Claxton (Lakota), Ashley Holland (Cherokee), Jennifer McNutt, and Tanya Willard (Secwepmc Nation) – provide readers with smart and often insightful consideration of relevant artworks and issues that the artists raise. Most will be familiar with Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun’s unflinching paintings and their critique of colonialism, political corruption, and resource extraction, but some may be less familiar with the other artists in Red.

McNutt’s analysis of Julie Buffalohead’s prints makes plain their profound, open-ended, and uncanny beauty: sensitively modelled negative spaces house a series of animal and doll figures, which subtly deride Euro-American notions of human-centred reality. Austere, restrained, surrealistic, each work is at once disarming and intimate, but also devastatingly critical. Similarly, Willard’s piece on Nicholas Galanin questions well the implications of contemporary Indigenous artists working in the interstices between, on the one hand, traditional (or customary) materials, techniques, and purposes, and, on the other, a myriad of new possibilities offered by emerging technologies, innovative materials, and cultural collisions. Galanin’s playful cultural mashups resonate in the deadly serious baskets of Shan Goshorn, woven in a tradition Cherokee manner but with startling materials. Case in point, for the piece entitled Educational Genocide – The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, the artist weaves a coffin-shaped basket from the pictures of children interned at the institution as well as text taken from a speech by Col. Richard Henry Pratt, in which he famously urged such institutions to “Save the man, kill the Indian.” Similarly, the photo-based work of Meryl McMaster – daughter of the renowned artist and curator Gerald McMaster – delves into questions of identity, culture, and the body, which play out in liminal spaces.

On the whole, Red is well designed, reasonably well illustrated, and thoughtfully written. In a couple of instances, artworks important to the essay and to understanding the artist’s career were not shown (this is especially frustrating in the omission of Goshorn’s Educational Genocide). Also, I question the use of cursive type to indicate a quotation by an artist, for the simple reason that it was difficult to read, but also that its intended purpose to lend a sense of the personal was undercut by its use with more than one artist. Those small critiques aside, this text will be a useful addition to any library that collects books on contemporary Indigenous art.

REFERENCES

Deloria, Jr., Vine. 1973. God is Red: A Native View of Religion. New York: Grosset and Dunlap.

––––––––. 1995. Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact. New York: Scribner.

Publication Information

Red: The Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship, 2013

Jennifer Complo McNutt and Ashley Holland, editors.

Indianapolis: Eitilijorg Museum, 2014. 136 pp. n.p. paper.