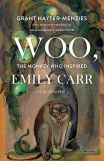

Woo, The Monkey Who Inspired Emily Carr: a Biography

Review By Maria Tippett

June 11, 2019

BC Studies no. 203 Autumn 2019 | p. 161-162

“Monkey Business: Emily Carr’s Woo”

In 1923 Emily Carr sent her maid, Pearl, to Lucy Cowie’s pet shop in downtown Victoria. She gave the owner thirty dollars and one of Carr’s Griffon dogs in exchange for a Javanese monkey. While visiting the pet shop a day or two earlier Carr had witnessed the monkey being bullied by her fellow primates and, as the Victoria artist later wrote in The Heart of a Peacock(176), ‘Suddenly I wanted her – I wanted her tremendously.’

Thus began a fourteen year long relationship between fifty-one year old Emily Carr and two year old Woo, as Carr called her new pet.

Grant Hayter-Menzies’s Woo, The Monkey Who Inspired Emily Carr,begins with Carr’s long interest in primates – as a student she observed monkeys at the London Zoo in Regent’s Park. He then goes on to tell us how ‘Woo the jungle creature offered what Carr termed a “foreign, undomestic note” in a setting she considered drab and workaday.’ (54) And, more significantly, how Woo ‘ . . . became Carr’s guide into a part of her self which, like the forests of British Columbia, she had to visit in order to become the artist she was meant to be.’ (71) Moving into the realm of creative fiction, the author makes even greater claims for Woo’s contribution to Emily Carr’s artistic development by the artist entering her Simcoe Street studio and encountering Woo, paintbrush in hand, in front of her easel: ‘. . . Carr gazes at Woo’s splash of sky, and wonders, with her, what new thing unfurls itself there, a reality she has sought and never found – till now.’ (78)

Coming back down to earth, Grant Hayter-Menzies then attempts to understand why Carr gave Woo to the Stanley Park Zoo in 1937 and what the animal might have encountered during her year there: ‘It is hard to deny that of all the places where Woo could have been the Monkey House at Stanley Park Zoo was the worst possible choice.’ (121) This leads Grant Hayter-Menzies to wonder whether Carr was ‘ . . . an ideal pet guardian.’ (129)

These and other suppositions rest on fact and fiction, on scientific research (Jane Goodall’s name is invoked more than once), on the author’s knowledge of animal shelters like Story Book Farm Primate Sanctuary in Sunderland, Ontario and, finally on the belief that primates like a capuchin monkey called Pockets Warhol who has produced hundreds of paintings and is ‘one of the top-selling animal artists in the world’ are creative. (142)

The extent to which Woo helped Carr to “see” during less than fifteen years together might have been examined alongside other factors. For example, Carr’s encounter with Seattle artists Ambrose and Viola Patterson in the middle of the 1920s and towards the end of that decade with Mark Tobey, Lawren Harris and F. B. Housser played a part in shaping her vision of Indigenous peoples and the west coast landscape as did her exploration of Theosophy and other non-traditional religions.

Equally, the author’s view that Carr was not the animal loving person that she claimed to be in her fictional and autobiographical writings must be considered within the context of the era in which she lived. Today’s pet loving owners subject their animals to medical procedures, medications and frequent trips to the vet. During the period in which Carr lived, she and her contemporaries were more pragmatic – and less emotional – when it came to the care of their animals.

Emily Carr was a complex woman. And, it must be remembered, during the years that she shared her life with Woo she was in poor health. Judging her life and her art through today’s values is nothing less than monkey business.

Publication Information

Woo, The Monkey Who Inspired Emily Carr: a Biography

Maderia Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019. 192 pp. $22.95 paper.