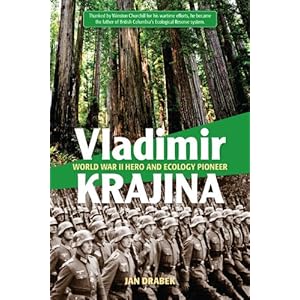

Vladimir Krajina: World War II Hero and Ecology Pioneer

Review By Iain Taylor

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 179 Autumn 2013 | p. 212-214

This book is a major addition to our understanding of Vladimir Krajina’s life and times because it provides a clear context to the life of this remarkable citizen. Jan Drabek’s father and Krajina played different but vital roles in the Czechoslovak resistance to the Nazis and the German occupation of Eastern Europe, before and during the Second World War. Their success was most evident in opening and maintaining lines of communication to the Western Alliance, although we may never know the real value of their work because the Czech operations were directed to action while avoiding detection.

Drabek’s introductory chapter sets the scene magnificently by telling of his childhood uncertainties about his family’s friend, Vladimir Krajina, and then provides a clear understanding of Krajina’s lifelong obsessions: his devotion to family and friends, the fundamentals of democracy, and the ecology of forests. The book’s first section brings us quickly to the Second World War, and Drabek’s narrative shows us how Krajina’s survival depended on his success in creating his own good luck. Krajina should have been arrested and executed several times but, even when they did arrest him, the occupying forces seemed convinced that he was much more useful alive than dead. They were rarely able to get more information out of him than they already knew. It is clear that throughout the war Krajina never betrayed a friend, in spite of treatment that would have broken most people. Perhaps his success lay in keeping a low profile and never knowing more than was essential to keeping the cause alive.

I arrived at the University of British Columbia in 1968. Krajina made me welcome, maybe because he hoped that he could recruit a young laboratory scientist to join in his search for elusive answers to questions about how plants have found their niches in an ecosystem. The second part of the book deals with the development of his research agenda, particularly his efforts to understand the whole ecosystem. He recognized British Columbia’s opportunities for both large-scale ecological study and for more sustainable forest management. He used his training in the study of large-scale ecology to develop a map of Biogeoclimatic zones in British Columbia, which has survived with minor modifications to this day. Krajina was recognized internationally for identifying ecologically important sites, areas, or regions, and for his pioneering work to persuade foresters, politicians, and ecologists to establish them as “reserves” that could be left without management interventions that would render the forest natural resources unnatural. Although many still criticize both achievements as unrealistic, Drabek points to Krajina’s political skills, especially those that involved persuasion of senior management and influential politicians. More than 100 ecological reserves exist that are set aside under British Columbia’s legislation, although research ecologists have yet to develop ways to use these protected areas. His legacy lives on through his students and others who collaborated in laying the foundations for future work to understand the complexity of British Columbia’s terrestrial ecosystems.

Vladimir Krajina: World War II Hero and Ecology Pioneer

By Jan Drabek

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2012. 200 pp, $21.95 paper