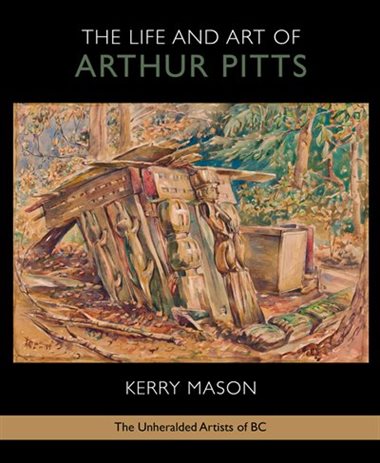

The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts

Review By Maria Tippett

March 10, 2018

BC Studies no. 197 Spring 2018 | p. 174-5

Kerry Mason begins The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts with a question: ‘Why haven’t I heard about this artist?’ (x) By the end of the book the reader is persuaded that we should indeed take Pitts seriously, though precisely why remains open to further discussion.

Kerry Mason begins The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts with a question: ‘Why haven’t I heard about this artist?’ (x) By the end of the book the reader is persuaded that we should indeed take Pitts seriously, though precisely why remains open to further discussion.

Born into an impoverished British family in 1889, Pitts apprenticed as a learner designer while taking night courses at the London City Centre School of Arts. By 1910 he was a fully qualified commercial artist, or in Edwardian parlance a show-card writer. He subsequently sold his humorous sketches and line drawings to newspapers and magazines while living in England, South Africa and Canada. He worked for various advertising agencies. And, in his spare time, he painted and took photographs.

In South Africa he photographed Zulu men and women: dancing, threshing grain, building huts and weaving baskets, and he collected their ‘native curios.’ (15) After arriving in Canada in 1914, Pitts followed George Catlin, Paul Kane and Emily Carr by recording Indigenous people and their villages up and down the coast of British Columbia. Confident that his ‘Indian Collection’ would be of interest to British collectors and galleries, he returned to his homeland in 1935. However, the prospects of generating interest only resulted in a small exhibition at Selfridges department store in London. Applying the “vanishing theme” to London’s streets and buildings proved to be more profitable. In 1946 Puttick & Simpson bought his entire series. This enabled Pitts to return to Victoria where he lived with his wife Peggy until his death in 1972. But the question remains: why could Pitts not make it as a full-time artist?

Like E.M. Forster’s impoverished clerk Leonard Bast in the novel Howard’s End (1910), Pitts was culturally and socially an outsider. True, he was a member of the Victoria Sketch Club and the Island Arts and Crafts Society. But so were many other amateur artists. True, he took evening courses at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts and spent six months at London’s Westminster School of Art. But this hardly put him at the cutting edge: he had studied at London’s most traditional art school and with Vancouver’s most traditional artist, Charles Scott. True, many artists, like the Ontario Group of Seven, began their careers as illustrators. But, unlike Pitts, they were able to leave their advertising jobs and to establish themselves as full-time artists. True, once again, Pitts recorded Indigenous people when that subject was not popular. But the paintings he produced in the 1930s are stylistically little different from the unimaginative work which Carr painted before her encounter in 1910 with Fauve and Expressionist artists in Paris. (Pitts’ ‘Indian Collection’ did not find a home until the provincial museums in Victoria and Calgary divided the paintings between themselves in the early 1950s.)

I am not suggesting that Arthur Pitts is unworthy of investigation, and I certainly acknowledge that, thanks to her use of a large collection of diaries, Mason has given a cogent year-by-year account of his life. I do, however, think that Arthur Pitts’ career path, rather like that of Leonard Bast, might also be viewed as a sociological phenomenon bound by his class origins, limited by his lack of connections, and (frankly) constrained by his own innate talent. All of this helps us to understand why most readers had never heard of Arthur Pitts until this study became the tenth volume in a series that is aptly named The Unheralded Artists of BC.

Publication Information

The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts

Kerry Mason

Salt Spring Island, BC: Mother Tongue Publishing Limited, 2017.142 pp. $35.95 softcover.