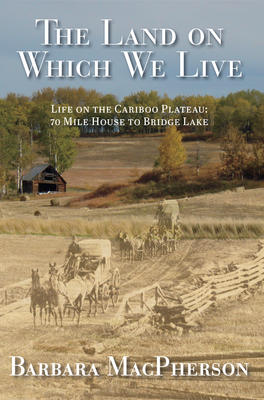

The Land on Which We Live: Life on the Cariboo Plateau: 70 Mile House to Bridge Lake

Review By Tina Block

February 4, 2019

BC Studies no. 203 Autumn 2019 | p. 156-157

In recent years, the historiography of British Columbia has burgeoned. Much of this rich and growing scholarship focuses on the province as a whole, or on its urban centres. We still have much to learn about the distinct experiences and histories of those who lived in British Columbia’s small towns and rural areas. In its exploration of life on the Cariboo Plateau, Barbara MacPherson’s The Land on Which We Live offers an important and welcome addition to the existing historiography.

In recent years, the historiography of British Columbia has burgeoned. Much of this rich and growing scholarship focuses on the province as a whole, or on its urban centres. We still have much to learn about the distinct experiences and histories of those who lived in British Columbia’s small towns and rural areas. In its exploration of life on the Cariboo Plateau, Barbara MacPherson’s The Land on Which We Live offers an important and welcome addition to the existing historiography.

The Land on Which We Live foregrounds the experiences of those people who lived between 70 Mile House and Bridge Lake from the early settlement era to 1959, when technological innovations began to make inroads into, and to fundamentally change, life in Cariboo communities. Drawing on an impressive range of sources, including land records, town directories, vital statistics, cemetery records, memoirs, newspapers, and interviews, MacPherson sets out to identify everyone who resided in the region, if even briefly, during the era under consideration. The book opens with a broad view on the landscape and settlement of the Cariboo Plateau, and with a discussion on the history and culture of the region’s first peoples, the Tsq’escenemc. The chapters that follow provide a detailed look at the process of land settlement, the establishment of the roadhouses, and the chief economic activities in the area. MacPherson effectively captures the difficulties involved in settling and working the land in a place with such severe winters and a relatively short growing season. Indeed, many settlers struggled to fulfill their agricultural and ranching aspirations and stayed only for a short time in the Cariboo before moving on. While much of the book centres on the relationship between settlers and the land, several chapters are also dedicated to aspects of social and community life in the region including leisure activities, women’s roles, health care, schooling, and voluntary organizations. Woven throughout the book, and at its heart, are the rich, compelling stories of the families who settled, or attempted to settle, in the various communities and sub-regions of the Cariboo Plateau.

The Land on Which We Live is a finely grained work of local and family history. MacPherson complements the text with photographs from the time, and integrates extensive primary source material, including excerpts from memoirs of, and interviews with, people who lived in the region. The book’s appendix, which outlines the history and trajectory of all of the families identified by MacPherson, will prove a valuable resource for others interested in conducting research on the area. While rich in detail about the lives of particular people in a specific region, this book also offers broader insights, not least of which is that place matters. According to MacPherson, the “Cariboo Plateau was a place that shaped and formed those who lived there” (17). In this book, the Cariboo Plateau is not the backdrop to, or container for, historical events and processes that could have happened anywhere. Instead, it is an actor in this story, a place with a distinctive landscape and history that shaped and reflected the people who lived in and were drawn to it. MacPherson shows the significance of the “land on which we live” to who we are, at not only the national and provincial but also the local level. Although she reveals the deep attachment to the land felt by many residents of the region, MacPherson does not romanticize the place or its peoples. In The Land on Which We Live, the Cariboo Plateau appears as a place of both life and death, success and struggle, joy and frustration – and, often, as a place where expectations and realities did not meet. While the book nicely captures the complexity of life on the Cariboo Plateau, it would be enriched by further attention to the culture and history of the Secwepemc peoples, and to Indigenous-settler relations in the region beyond the settlement era. In addition, religion and the churches get scant mention in the book, which perhaps speaks to the comparatively secular character of the region and of British Columbia as a whole. Further discussion on the role (or lack thereof) of religion and the churches in the communities of the Cariboo Plateau would deepen our understanding of how and why this place was, and is, distinctive.

The Land on Which We Live makes an important contribution to local history in British Columbia. Filled with family stories, this book will be of special interest to those who reside, or have resided, in the region. Historians of British Columbia will find the book useful for the detailed history it offers and for its rich appendix and primary source bibliography. It is recommended reading for anyone interested in the history of settlement, labour, the family, and rural society in British Columbia.

Publication Information

The Land on Which We Live: Life on the Cariboo Plateau: 70 Mile House to Bridge Lake

Barbara MacPherson

Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2017. 240 pp. $24.95 paper.