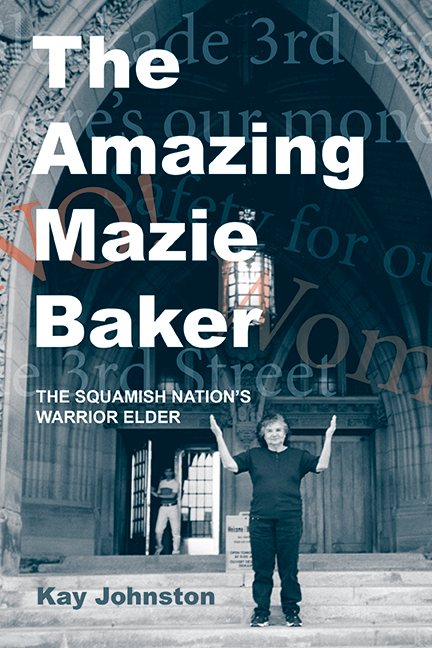

The Amazing Mazie Baker: The Squamish Nation’s Warrior Elder

Review By Sean Carleton

March 11, 2017

BC Studies no. 196 Winter 2017-2018 | p. 156-158

I grew up ten minutes away from Eslha7án, the Mission Indian Reserve, in what is today known as North Vancouver, which is part of the territory of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw or Squamish Nation. Yet I did not learn a lot as a child about Indigenous peoples generally or about Squamish people specifically. Kay Johnston’s book, The Amazing Mazie Baker, gave me, and will give other readers, the opportunity to see the “north shore” from the perspective of a woman warrior Elder of the Squamish Nation – Mazie Baker. For much of her life, Mazie fought for the rights of Squamish people, and particularly to protect and create opportunities for Indigenous women. The book is a rich collection of stories that Mazie shared with Johnston, ranging from how she escaped residential school and crossed the border to live and work in Washington with her family, to her political struggles back home against the patriarchal policies of band and settler governments. The Amazing Mazie Baker contributes to the growing record of Indigenous peoples telling stories of resistance, resilience, and resurgence, and the book will be of interest to those studying women’s and gender history, Indigenous feminisms, and political organizing in colonial contexts.

I grew up ten minutes away from Eslha7án, the Mission Indian Reserve, in what is today known as North Vancouver, which is part of the territory of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw or Squamish Nation. Yet I did not learn a lot as a child about Indigenous peoples generally or about Squamish people specifically. Kay Johnston’s book, The Amazing Mazie Baker, gave me, and will give other readers, the opportunity to see the “north shore” from the perspective of a woman warrior Elder of the Squamish Nation – Mazie Baker. For much of her life, Mazie fought for the rights of Squamish people, and particularly to protect and create opportunities for Indigenous women. The book is a rich collection of stories that Mazie shared with Johnston, ranging from how she escaped residential school and crossed the border to live and work in Washington with her family, to her political struggles back home against the patriarchal policies of band and settler governments. The Amazing Mazie Baker contributes to the growing record of Indigenous peoples telling stories of resistance, resilience, and resurgence, and the book will be of interest to those studying women’s and gender history, Indigenous feminisms, and political organizing in colonial contexts.

The book is structured into clusters of stories and anecdotes about different periods of Mazie’s remarkable life. Velma Doreen “Mazie” Antone was born to Moses and Sarah Antone in 1931 at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. Like many Indigenous children, Mazie could not avoid being forced to attend residential school. In 1920 the federal government amended the Indian Act to make attendance mandatory, and in 1937 the police came to take young Mazie to St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in North Vancouver. There she was forced to perform manual labour and was often abused by school staff. Mazie later recalled, “I was scared and angry. I just knew this was wrong and unfair, and I made this very clear to the Sisters by just refusing to cooperate….I tried my best to be difficult. Stubbornness was my way of fighting things I didn’t want to do or if I was scared. I just wanted to go home” (23). Mazie’s “stubbornness,” in school and afterward, became her signature character trait and might be understood as a form of what Anishinaabe cultural theorist Gerald Vizenor (1994) calls “survivance,” a mixture of survival and resistance.

When Mazie’s parents became aware of the school’s inexcusable treatment of their children, they took direct action. Mazie recalled the day her mother came to the school to rescue her and her siblings, declaring to one of the Sisters, “Look, if you don’t want to be laying in a ball at the bottom of the stairs, you’d better get out of my way, ’cause I’m taking my kids home, and there’s no way you’re going to stop me” (27). The Antones made the difficult decision to leave their community and escape to Washington where they worked picking hops and berries. Scholars like Paige Raibmon (2005) and Michael Marker (2015) have shown that Coast Salish peoples have always traversed the colonial border between Canada and the United States, and the Antones’ actions confirm that Coast Salish cross-border migration continued well into the twentieth century. Mazie’s stories of escaping residential school and working in Washington also highlight the ingenuity and agency of Mazie and her family.

After a number of years in Washington, Mazie’s family returned to the reserve. Like many Squamish men at the time, Moses found work as a longshoreman, and Sarah and some of her children, including Mazie, worked at a local cannery. Mazie soon met and married Alvie Baker and raised a family on the Mission Indian Reserve. But it was not until she became involved in political organizing later in life that Mazie felt that she really came into her own. As a survival strategy, Mazie’s father had downplayed his cultural roots, but this meant that Mazie was largely disconnected from Squamish culture for much of her life. Mazie wanted her own children to understand what it meant to be Squamish and began advocating for cultural revival on the reserve, putting special emphasis on language education for youth. Her efforts made her a number of enemies who preferred the status quo, and she quickly developed a reputation as a troublemaker. But Mazie never took “no” for an answer, and this made her an excellent advocate for the Squamish people and culture. She also worked with a number of other Squamish women to protest patriarchal policies of the male-dominated band council, and she fought municipal, provincial, and federal laws to increase the power of the Squamish people, and especially of Squamish and other Indigenous women. While Mazie died in 2011, the power of her stories lives on in Johnston’s book and will continue to offer a number of important lessons for those interested in Indigenous women’s political organizing in Canada. These stories of struggle and survival are worthy of wider recognition and critical reflection in today’s era of so-called reconciliation.

References

Marker, Michael. 2015. “Borders and the borderless Coast Salish peoples: Decolonising historiographies of Indigenous schooling.” History of Education: Journal of the History of Education Society 44 (4): 480–502.

Raibmon, Paige. 2005. Authentic Indians: Episodes of Encounter from the Late-Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Vizenor, Gerald. 1994. Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Publication Information

The Amazing Mazie Baker: The Squamish Nation’s Warrior Elder

Kay Johnston

Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2016. 230 pp. $24.95 paper.