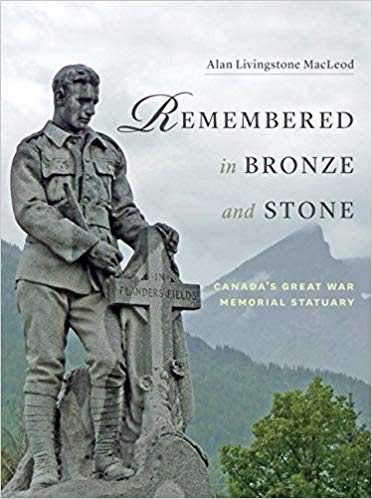

Remembered in Bronze and Stone: Canada’s Great War Memorial Statuary

Review By Maria Tippett

March 24, 2017

BC Studies no. 196 Winter 2017-2018 | p. 146-148

In the two decades following the Great War, Canadian sculptors, architects and stonemasons produced over four thousand war monuments in the form of plaques, shafts, crosses, obelisks, stelae and figurative sculptures. Some were paid for by federal and provincial governments; others by civically minded organizations. Whatever form they took, war memorials provided fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters throughout Canada with a site for grieving, remembering and celebrating those who did not survive the Great War. Above all, the production of war memorials gave the sculptors who made them a means of earning a living during the financially lean inter-war years.

In the two decades following the Great War, Canadian sculptors, architects and stonemasons produced over four thousand war monuments in the form of plaques, shafts, crosses, obelisks, stelae and figurative sculptures. Some were paid for by federal and provincial governments; others by civically minded organizations. Whatever form they took, war memorials provided fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters throughout Canada with a site for grieving, remembering and celebrating those who did not survive the Great War. Above all, the production of war memorials gave the sculptors who made them a means of earning a living during the financially lean inter-war years.

In Remembered in Bronze and Stone, Canada’s Great War Memorial Statuary, Alan Livingston MacLeod focuses on the more than 410 figurative war memorials that can be found in villages, towns, and cities across the country today. MacLeod has visited – and photographed – them all. And the results are a revelation. There are grenade-throwing and bayonet-stabbing soldiers. There are also pensive and reflective soldiers like the grieving soldier sculpted in Fernie, British Columbia. There is Canada’s elaborate National War Memorial in Ottawa featuring a cavalcade of uniformed men and women marching through a commanding arch. Then there is the largest of all: the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, with its two 230-foot-high pilons, tonnes of stone and granite, and imposing allegorical figures, that commands the ridge above the Dauoi Plain in southeastern France.

The war memorials featured in this handsome volume were rendered in a plethora of styles ranging from the Beaux-Arts and Art Nouveau traditions of the late nineteenth century to the Art Deco style that came to prominence during the 1920s. And the artists who created these figurative works came not only from Canada, but also from Great Britain and Italy. Indeed, as MacLeod reveals, anonymous artists in Carrera, Italy, produced almost half of Canada’s figurative war memorials. This accounts for why MacLeod found Canadian soldiers wearing soft, rather than hard, hats; striking stiff stand-to-attention poses; and wearing uniforms with a disturbing similarity to those worn by New Zealand and Australian soldiers.

Alan MacLeod is not just interested in what was represented on top of the plinth. He tells us about the soldiers whose names are featured at the base of the plinth. For example, he writes movingly about a young bank clerk from Dorchester, Ontario, who enlisted when he was just seventeen. Lance-Corporal Harvard McAllister survived four years on the front line only to be killed in Hangard Wood just three months before the end of the hostilities. MacLeod underscores the distance between young men like McAllister whose remains were buried in the Demuin British Cemetery on the Somme, and their homes in Canada. Accounts like this give additional meaning to the hundreds of memorials that Canadians pass by every day.

Of course, not all memorials were figurative. For example, to commemorate the fifty-four Canadians of Japanese ethnicity who had volunteered and died on the Western Front, the Japanese community in Vancouver raised funds for their own memorial. The result, the Japanese Canadian War Memorial, erected in Stanley Park in 1920, merged a western column with ancient Kasuga lanterns typical of the famous shrine in Kyoto.

Nor did the figurative sculptures that were produced during the Great War always commemorate the fighting forces. Sculptors Frances Loring and Florence Wyle showed that there were other kinds of heroes, when they depicted the women who worked in the factories and munitions plants during the course of the war. Commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Fund during the closing years of the Great War, Wyle and Loring’s sculptures showed that women were not just allegorical figures or victorious angels – as they were represented on plinths across the country – but contributors to the war effort on the home front. However, MacLeod’s focus in Remembered in Bronze and Stone, Canada’s Great War Memorial Statuary is on the fighting forces, and he does an admirable job of showing us how they were remembered.

Publication Information

Remembered in Bronze and Stone: Canada’s Great War Memorial Statuary

Alan Livingston MacLeod

Victoria: Heritage House Production, 2016. 192 pp. $24.95 paper