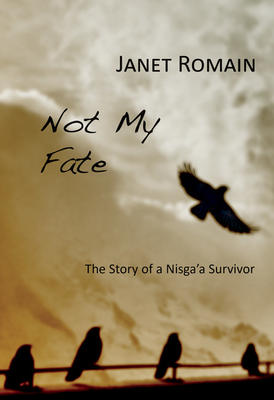

Not My Fate: The Story of a Nisga’a Survivor

Review By Carole Blackburn

June 5, 2018

BC Studies no. 199 Autumn 2018 | p. 187-8

Not My Fate: The Story of a Nisga’a Survivor is Janet Romain’s account of the life of her friend and fellow northerner, Josephine Caplin.[1] Jo was born in Smithers to a Nisga’a mother and non-Aboriginal father. At the outset we learn that Jo’s mother, a residential school survivor originally from the Nisga’a village of Gingolx, was not part of Jo’s life. Jo’s earliest years were spent in logging and mining camps across northern B.C. with her father, uncle and beloved brother Sam. While Jo and Sam did a good job of looking out for each other, Jo was soon put into foster care. Jo then lives through several different foster homes until she is able to return to her family in her early teens. As Jo’s life unfolds she leaves school to work and live across northern B.C., the lower Mainland and Alberta. She is a model employee and hard worker but suffers from traumatic epileptic seizures. Married for the first time at 15, she makes the heartwrenching decision to give up her infant son as her husband, whom she leaves, becomes increasingly violent and her blackouts from the seizures become more debilitating.

Not My Fate: The Story of a Nisga’a Survivor is Janet Romain’s account of the life of her friend and fellow northerner, Josephine Caplin.[1] Jo was born in Smithers to a Nisga’a mother and non-Aboriginal father. At the outset we learn that Jo’s mother, a residential school survivor originally from the Nisga’a village of Gingolx, was not part of Jo’s life. Jo’s earliest years were spent in logging and mining camps across northern B.C. with her father, uncle and beloved brother Sam. While Jo and Sam did a good job of looking out for each other, Jo was soon put into foster care. Jo then lives through several different foster homes until she is able to return to her family in her early teens. As Jo’s life unfolds she leaves school to work and live across northern B.C., the lower Mainland and Alberta. She is a model employee and hard worker but suffers from traumatic epileptic seizures. Married for the first time at 15, she makes the heartwrenching decision to give up her infant son as her husband, whom she leaves, becomes increasingly violent and her blackouts from the seizures become more debilitating.

Jo is entitled to Nisga’a citizenship through her mother but has lived her life off of Nisga’a lands. British Columbians may be familiar with the Nisga’a treaty and the events leading up to it, including the work of Frank Calder and the Nisga’a Tribal Council in pursuing recognition of unextinguished Aboriginal title in British Columbia. In 2000 the Nisga’a treaty became the first modern day treaty made in British Columbia. None of this features in Jo’s story, and the coming into effect of the treaty has little to no impact on her life. Readers looking for any connection with these events will not find it in this account. Romain intersperses Jo’s story with reflections on other political events, however, including Idle No More, pipeline development in northern B.C, and most significantly, residential schools.

The intergenerational impact of residential schools on Aboriginal families and communities is a central theme of this book. Jo’s mother and grandmother were both residential school survivors, and we see how the effects of their experiences are passed on into the lives of Jo and her brother. Jo herself becomes a victim of abuse and has to give up her child, but in other ways has forged a life that takes her out of the cycle of the intergenerational effects of trauma. Jo identifies herself as a survivor, not a victim. Readers will appreciate Jo’s garden, which features prominently in this narrative, not just as wonderfully bountiful but also as a way that Jo cares for herself and connects with the people and the land around her.

This book is best in its compassionate and graceful telling of Jo’s story, mixed with reflections on northern life. Readers will find it a timely book in light of the recent Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the current political emphasis on reconciliation in Canada.

Not My Fate: The Story of a Nisga’a Survivor

Janet Romain

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2016. 256 pp. $24.95 paper.

[1] This is a pseudonym.