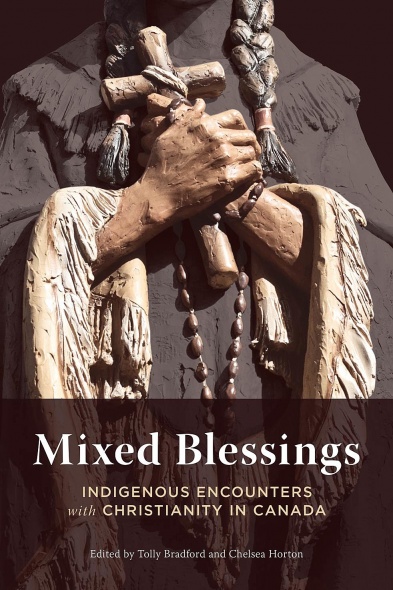

Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada

Review By Dorothy Kennedy

March 13, 2018

BC Studies no. 197 Spring 2018 | p. 167-9

Mixed Blessings is a collection of papers developed for a May 2011 workshop, “Religious Encounter and Exchange in Aboriginal Canada,” capably edited by historians Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton, whose helpful introduction and conclusion pull together the disparate interests of the contributors. The collection does not claim comprehensiveness either in theoretical scope or in geographical coverage (12), yet, considering the uneven quality of the articles, I would quibble with the editors’ promise that the volume offers a “fresh way forward” (12). I would instead highlight their view that readers “should approach this collection as a reconnaissance project that seeks both to sketch out basic terrain and encourage ongoing research and dialogue” (4). Cognizant of that more modest self-appraisal, I found the collection appealing, for it does allow one to gauge interdisciplinary interest and approaches to the topic in Canada.

Mixed Blessings is a collection of papers developed for a May 2011 workshop, “Religious Encounter and Exchange in Aboriginal Canada,” capably edited by historians Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton, whose helpful introduction and conclusion pull together the disparate interests of the contributors. The collection does not claim comprehensiveness either in theoretical scope or in geographical coverage (12), yet, considering the uneven quality of the articles, I would quibble with the editors’ promise that the volume offers a “fresh way forward” (12). I would instead highlight their view that readers “should approach this collection as a reconnaissance project that seeks both to sketch out basic terrain and encourage ongoing research and dialogue” (4). Cognizant of that more modest self-appraisal, I found the collection appealing, for it does allow one to gauge interdisciplinary interest and approaches to the topic in Canada.

It was once thought that works about missionaries and Indigenous people should be focused on the missionary-as-hero or missionary-as-villain or on the White colonizer/Indigenous victim binary. However, studies of the encounter have now shifted towards examining a more layered and contested history, illuminating the reformulation of the Native American religious landscape and the complex role of individual missionaries and converts. Examples of this more nuanced approach which have advanced scholarly understanding of the missionary encounter in British Columbia include studies by Neylan (2003), Brock (2011), Bradford (2012) and Robertson (2012), as well as articles by Galois (1997/98), Tomalin (2007), and Lowman (2011) appearing in BC Studies.

The editors have divided Mixed Blessings into three parts: 1) Communities in Encounter; 2) Individuals in Encounter; and 3) Contemporary Encounters. Authors in the first part examine religion as a locus of cross-cultural communication and contested power. Drawing upon seventeenth-century Jesuit records, Timothy Pearson explores how the performance rituals of the Hurons and Algonquins in early contact zones built upon an existing social solidarity and attempted to generate a shared experience of sacred power to all willing participants, missionaries included; in contrast, the Christian priests used ritual to exclude the uninitiated, mirroring such discriminatory attitudes in their written texts. The importance of ritual to strengthen community unity is also a theme of Elizabeth Elbourne’s article. She examines the Haudenosaunee’s use of Anglicanism to broker ties with the British, along with the political implications of their varying degrees of religious expression. The third contribution, by Amanda Fehr, discusses how a Stó:lō community in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley erected a granite Christian memorial as an innovative means to articulate identity and assert territorial claims in the 1930s.

Part Two begins with Cecilia Morgan’s look at the engaging story of the marriage of a devotedly evangelical English woman, Eliza Field, to Peter Jones, a mixed-race Mississauga missionary, illustrating how the encounter for this nineteenth-century missionary couple was both intimate and transnational. Inspired by recent publications in the field of the sociology of religion, Jean-François Bélisle and Nicole St. Onge bring to the fore the religious content of Louis Riel’s thought, thus emphasizing the importance of religion as one of the central dimensions of Métis interrogation of colonialism, and highlighting how Riel’s redefinition of the world was “constructed on the basis of a geopolitically reconfigured faith” (113). This article breaks new ground and is a welcome addition to the volume. Part Two ends with Tasha Beeds’s summary of the intellectual legacy of Cree-Métis missionary Edward Ahenakew. Beeds states that she consciously attempts to work “on the inside of language” (119), as Kiowa writer Scott Momaday has proposed. However, as worthy as the Ahenakew story and attention to both his Cree and Christian foundations may be, Beeds’s profuse use of Cree terms, employed without the linguistic insights or masterful prose that are central to Momaday’s approach, becomes distracting. Nothing is gained, for example, by using the term napêw instead of “man” or mâmitonêyihcikan, said to mean “thinking” (136-137).

Part Three, “Contemporary Encounters,” opens with Siphiwe Dube’s critical examination of religion’s role within the mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Using a series of piercing questions revealing Christianity’s ambiguous role as both offender and healer, Dube concludes that “the onus remains only on the wronged Indigenous communities to positively re-inscribe the religion in question (in this case Christianity) so that it still makes sense…” (159). No doubt this re-inscription will rely upon the methodologies and processes discussed by Denise Nadeau in her article that follows on teaching a course on Indigenous traditions. Nadeau suggests that instruction about colonialism through the lens of Indigenous knowledge systems exposes all students to a new world perspective and encourages self-reflection. The final article in Part Three is an auto-ethnographic account by Carmen Lansdowne, a member of the Heiltsuk First Nation and an ordained minister in the United Church of Canada. Lansdowne thoughtfully reflects not only upon the history of missionaries and lay preachers among her people and the scholarship that has illuminated this relationship, but also upon her frustration and discontent with the methodological limitations of that work.

Mixed Blessing is a highly readable update on what is happening in the field of missionary interactions. It exposes the silences – the factual voids in our understanding of the complex Indigenous encounters with Christianity in Canada – and for that reason, I recommend the book to those interested in achieving reconciliation.

Bradford, Tolly. Prophetic Identities: Indigenous Missionaries on British Colonial Frontiers, 1850-75. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

Brock, Peggy. Many Voyages of Arthur Wellington Clah: A Tsimshian Man on the Pacific Northwest Coast. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011.

Galois, Robert M. “Colonial Encounters: The Worlds of Arthur Wellington Clah, 1855-1881,” BC Studies No. 115/116 (Autumn/ Winter 1997/98), pp. 105-149.

Lowman, Emma Battell. “`My Name is Stanley’: Twentieth-Century Missionary Stories and the Complexity of Colonial Encounters,” BC Studies No. 169 (Spring 2011), pp. 81-99.

Neylan, Susan. The Heavens are Changing: Nineteenth-Century Protestant Missions and Tsimshian Christianity. Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Robertson, Leslie A., and Kwagu’ł Gixsam Clan. Standing Up with Ga’axsta’las: Jane Constance Cook and the Politics of Memory, Church, and Custom. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

Tomalin, Marcus. “`My Close Application to the Language’: William Henry Collison and Nineteenth-Century Haida Linguistics,” BC Studies, No. 155 (Autumn 2007), pp. 93-128.

Publication Information

Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada

Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton, editors

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016. 226 pp. Illus., Index, $95.00 cloth, $29.95 paper