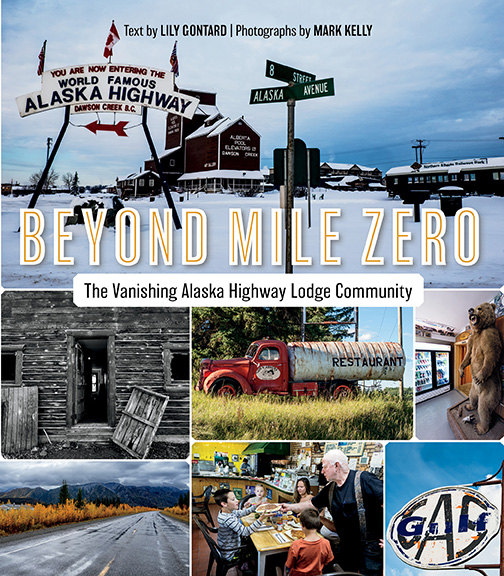

Beyond Mile Zero: The Vanishing Alaska Highway Lodge Community

Review By Steve Penfold

March 4, 2018

BC Studies no. 197 Spring 2018 | p. 181-2

The Alaska Highway runs from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction, Alaska. Built by the American military for defense purposes during the Second World War, it was opened to the public in 1948 and became a key spine of northern development. Resource companies, truckers, and tourists drove the road; roadside businesses grew up to feed off the traffic. Beyond Mile Zero is a portrait of the “Lodge Community” that served the road – the families, partners, and workers who made a living, and built their lives, beside the Alaska Highway.

The Alaska Highway runs from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction, Alaska. Built by the American military for defense purposes during the Second World War, it was opened to the public in 1948 and became a key spine of northern development. Resource companies, truckers, and tourists drove the road; roadside businesses grew up to feed off the traffic. Beyond Mile Zero is a portrait of the “Lodge Community” that served the road – the families, partners, and workers who made a living, and built their lives, beside the Alaska Highway.

Interviews with former and current lodge owners and several stunning colour photographs form the core of the book. Most lodges were (and remain) small family businesses, relying on husband-wife-children teams supplemented by hired staff during the summer. Owners tell of hard work and frustrations, but the book is mostly optimistic in tone, despite the word “vanishing” in the title. Most owners say that running a lodge made for a good life, while many photographs feature smiling husband-wife teams, well-stocked bakery counters, and quirky signs, serving to reinforce the generally affectionate tone of the text.

The “vanishing” in the title comes from the general recognition, articulated by several interviewees, that the heyday of the highway business has passed. In 1955, there was a service outlet every 25 miles, but sixty years later you had to drive at least four times that distance to find a business (26). Highway straightening and fuel efficient cars were two enemies of lodge culture: today, drivers go much faster, drive further in a day, and need to stop less frequently than before. The peak came in the early 1980s, when bus tours continued to fill parking lots along the highway. There was a temporary boom by the turn of the twenty-first century tied to petroleum development, but as one owner laments, “everything slowed up here two years ago…There’s virtually no activity in the oil field-related stuff – basically the operator just looks after the infrastructure.” For this owner, business has declined by 40 percent (51).

This kind of boom-bust cycle is different than the standard seasonal pattern of the lodge business, mentioned several times but not thoroughly explored in the book. In the heyday of the lodge, most owners closed down in winter but some stayed open all year. Beyond Mile Zero, however, focuses on the summer. Even the photographs mostly feature leafy stretches of road, with few parkas and winter boots in view.

The authors are correct that too many highway books focus on heroic builders rather than the ordinary people who made the road work over time. Beyond Mile Zero’s focus on lodge owners and community is welcome. By the end, the narrative structure does start to feel stale and standard – a family opens a lodge, bakes cinnamon buns, struggles with generators, enjoys the life, sells the business to someone else, and the cycle continues. You start to wish for something different or deeper, perhaps more reflection on what “community” means in the context of a highway. The term signals the human focus of Beyond Mile Zero, but what makes these geographically scattered families, who mostly pursue their own lives, into a “community”? Owners get to know a few regular customers, send their kids to nearby schools, and participate in bonspiels, but interviewees says little about connections to each other. Do lodge owners have common institutions, see each other, or make up a community of their own? The question is not really explored.

Overall, however, Beyond Mile Zero is a good read: an engaging and refreshingly human portrait of the roadside.

Publication Information

Beyond Mile Zero: The Vanishing Alaska Highway Lodge Community

Lily Gontard and Mike Kelly

Madeira Park, BC: Lost Moose (Harbour Publishing), 2017. 224 pp. $24.95 paper.